Talk to us,Get a Solution in 20 minutes

Please let us know any requirements and specific demands,then we work out the solution soonest and send back it for free.

Please let us know any requirements and specific demands,then we work out the solution soonest and send back it for free.

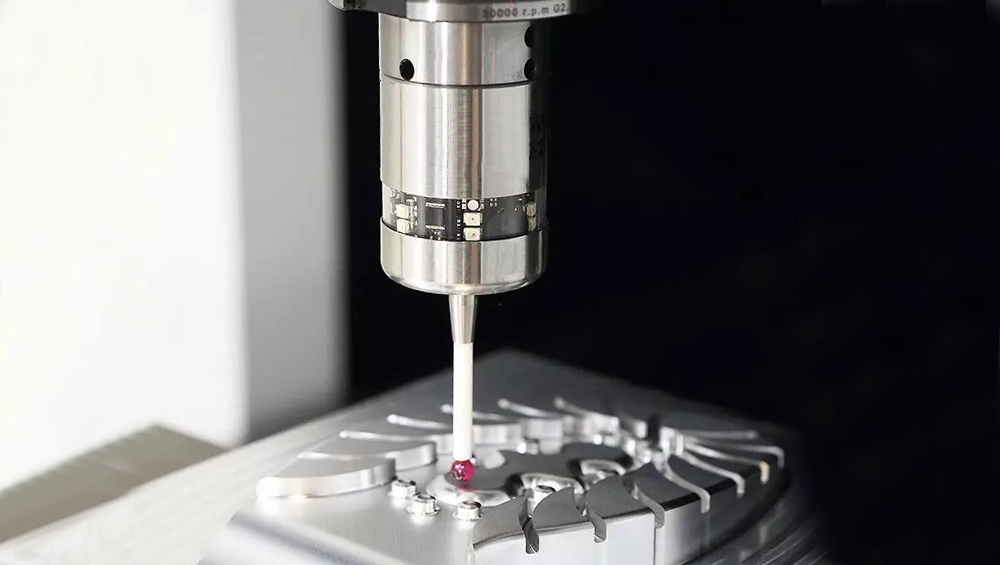

Finding a reliable 0,0,0 on your CNC — the point where X, Y, and Z all meet — is one of the first real steps to accurate machining. Whether you’re doing one-offs or production runs, nailing the zero means your program will hit features where it should. Traditionally, operators used edge finders, indicators, or simple visual alignment. But with a touch probe and the right approach — using plates, pucks, and probing routines — you get accuracy, repeatability, and confidence every time.

This isn’t about memorizing a macro — it’s about understanding why we use specific tools and sequences, and how to think like someone who trusts their machine instead of guessing.

In simplest terms, zeroing is establishing a known point on a workpiece — typically the corner, center, or surface that the rest of the program will reference. That point becomes the basis for your work coordinate system (G54, G55, etc.). If that point is even a few thousandths off, every move after it compounds that error. With a probe, zeroing isn’t guesswork, it’s measured data.

Learn more about CNC laser tool setters cnc-probe.

A probe plate is a precision metal plate placed on the machine table or on your workpiece. It gives a predictable, known surface that you use to find Z zero (defining work height). Because the plate thickness is known and consistent, once the probe makes contact, the controller can automatically calculate the true surface location using the plate thickness value entered in your probing routine.

This is a widely adopted approach because:

In practice, you run a probing cycle that lowers the tool to contact the plate, records the contact point, and then offsets Z zero based on the plate’s known thickness.

Explore CNC modular touch probes cnc-probe.

A probing puck is a solid block — often magnetic or fixtured in place — used to reference X and Y positions. It’s particularly helpful for:

Why pucks? Think about it like this: if the goal is to find X and Y zero, you’re essentially asking “where is this known point relative to my machine’s world?” With a puck you can approach it from different axes, probe its surface, and use those measured positions to mathematically determine true X/Y zero.

This approach removes a lot of the manual interpretation that edge finders require (you know, where you slowly creep until the dial moves) by letting the machine feel and record exact points.

Check out CNC transmission wired touch probes cnc-probe.

For many probing systems — whether you’re using a dedicated controller or practical macros — these routines follow a sequence that mirrors a common thought pattern on the shop floor:

Place the plate on the fixture or stock and secure it so it won’t shift. Make sure the puck or plate is clean and the connection back to the probe input is solid.

This is like tuning your instrument before playing — if the reference is unstable, everything that follows will be unreliable.

The typical probing sequence in many controllers (especially macro-driven or CNC software with probing support) starts by lowering until the probe contacts the plate or the surface of the part.

This establishes a baseline height.

It usually looks like:

The idea here is simple: define where the top of the workpiece is first. Without that, you can’t confidently set X/Y origins because Z is floating in uncertainty.

Once Z is known, the next steps are about X and Y:

This sequence minimizes error due to stylus deflection, probe pre-travel, and spindle runout. In other words, by measuring two opposite faces and averaging, you’re letting machine measurement dictate the zero, not human feel.

Learn more about CNC Z-axis wired tool setters cnc-probe.

You might wonder: “Why not just edge find or eyeball it?”

Here’s the deeper truth: manual methods rely on operator skill and variability. Two machinists might edge find the same part and get slight differences. A probe, with plates and pucks, reduces human interpretation and lets the machine’s encoders inform you of exact coordinates.

In modern manufacturing we’re after confidence and repeatability — reproducible data that any operator can run and trust.

Visit CNC Probe homepage cnc-probe.

One question that comes up often in practice is: “Do I have to probe again after a different cutting pass?”

The answer isn’t always yes — but often it’s wise:

The deeper insight here: probing isn’t one-and-done. You’re essentially validating your references throughout the process. When you lose confidence in your datum (tool change, fixture shift, vibration), probe again.

Explore high-precision measurement CNC probes cnc-probe.

Learn about CNC optical wired five-axis CNC touch tool setters cnc-probe.

Experienced operators think in terms of surfaces and reference geometry — not just G-code moves. What you’re really doing with probing is answering these questions:

Once you frame zeroing in that way, using plates, pucks, and routines starts to make intuitive sense.

Zeroing with a probe isn’t a magic trick. It’s a measurement strategy grounded in predictable contact points and consistent coordinates:

The machine becomes a metrology device, not just a cutting machine. That’s the difference between hoping your setup is good and knowing it is.